1. Arrival in Kerikeri: A First Impression Cloaked in Mist

A light mist rolled over the green hills as I turned off State Highway 10 into Kerikeri. Morning dew clung to the windows, and the trees bordering the road shimmered under a weak sun still mustering the courage to rise. The subtropical air held a gentleness that reminded me of early autumn mornings in the countryside—quiet, full of expectancy, and colored with shades of both memory and anticipation. A feeling washed over me that this place had long stood as a silent witness to stories greater than the trees, greater than the river, greater even than the modest buildings nestled alongside them.

Kerikeri lies in the Bay of Islands, in the far north of New Zealand, a region known for its lush landscapes, orchards, and deep Maori and colonial roots. While many come here for the coastal charm or the bounty of local produce, my own path had narrowed to a singular purpose: to visit the historic Stone Store and the adjacent Mission House, two structures that seemed to defy the passage of time, quietly holding their place while the world spun faster and faster around them.

2. Through the Trees and Across the River: A Path Worn by Time

The walkway leading to the Stone Store winds through trees so dense that the sound of footsteps disappears beneath the foliage. It is a short walk, not more than a few hundred meters, but it carries the weight of almost two centuries of history. The Kerikeri River murmurs nearby, flowing slow and steady beneath the arched footbridge. A white duck paddled near the bank, seemingly indifferent to the day’s visitors. Everything here had the mood of reverence—there was no need to rush.

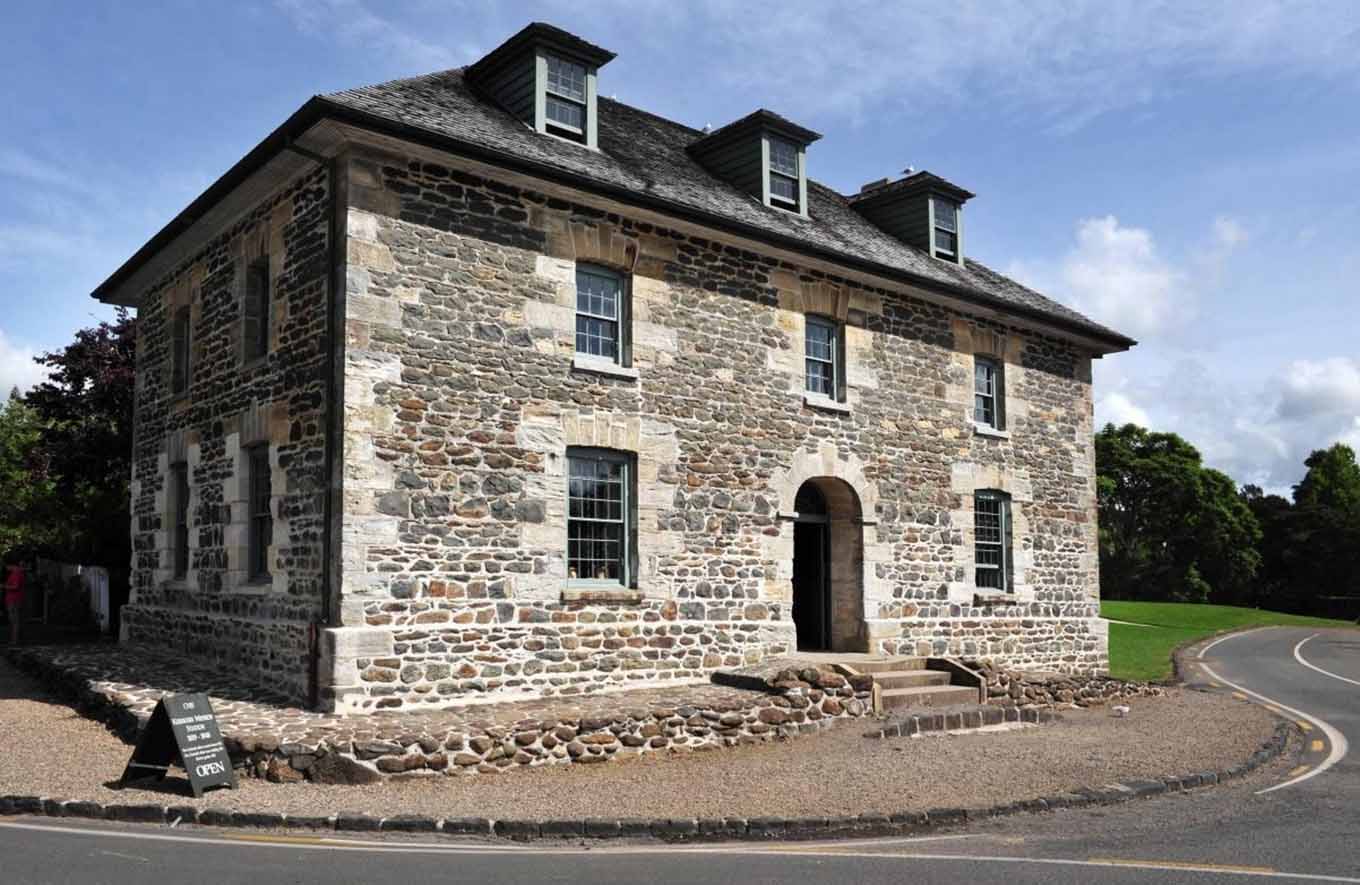

As the store came into view, its basalt walls seemed to catch the light differently from everything else around it. Not reflective, not absorbing—just holding it. Built between 1832 and 1836, the Stone Store is the oldest surviving stone building in New Zealand. Its Georgian style, unusual for this part of the world, appears as both an anomaly and a landmark—a testimony to the ambitions of European missionaries who sought not just to live, but to plant permanence in unfamiliar soil.

Next to it stands the Mission House, also known as Kemp House, a white weatherboard home completed in 1822 and still standing with grace and dignity. It felt as though time had paused its ticking when I stepped onto the gravel path between the two buildings. The trees leaned in as if to listen, and the river held its breath.

3. The Missionary Dream: Building Faith and Foundations

The roots of these buildings trace back to the arrival of the Church Missionary Society, an English Anglican mission that sought to spread Christian teachings among the Maori and introduce British civilization. Samuel Marsden, a key figure in early New Zealand history, had been instrumental in establishing missions in the Bay of Islands. The Kerikeri mission was one of the earliest and most enduring.

The Mission House was initially home to Reverend John Butler, the first ordained clergyman to reside in New Zealand. However, it later became the family home of James and Charlotte Kemp, whose descendants continued to live in the house for over 130 years. The Kemp family’s long occupancy preserved not only the physical structure but a lineage of daily life and memory that transcended the ordinary.

Walking into the Mission House is like stepping through a veil. The interior remains furnished much as it might have been in the late 19th century. Polished wood floors creaked underfoot. Simple wooden furniture stood in neat symmetry. A glass-fronted cabinet held books whose spines bore faded gold lettering. Every room whispered of both routine and ritual—the life of a household that balanced spiritual labor with domestic order.

There were no digital screens, no artificial sounds—just the rustle of leaves against the panes and the quiet hum of a day unfolding as it might have a hundred years ago. The kitchen, with its cast-iron stove and wooden shelving, offered the strongest echo of domestic life: bread once kneaded here, stew once stirred, children once hushed to silence. Time here was not abstract—it was measured in teaspoons, sermons, and the seasonal rhythms of the land.

4. The Stone Store: Commerce Meets Conviction

The Stone Store is more than an architectural curiosity—it was an experiment in stability during a time of uncertainty. Designed by Wesleyan missionary John Hobbs and built by ex-convict stonemason William Parrott, its walls rise thick and unyielding from the ground. It was built to house mission goods—flour, tools, cloth, books—and protect them from fire, rot, and war.

The first time I stepped through the arched door into the store, the cool air wrapped around me like a vault. The interior smelled of leather, aged wood, and dust—clean dust, the kind that settles only when things are left untouched for a long while. Heavy timbers stretched overhead like the ribs of a ship, and thick stone walls muffled the outside world.

Shelves lined the walls, holding replicas of goods once traded here: nails in wooden boxes, muslin cloth folded in stacks, barrels with worn staves. Today it is part shop, part museum, but the care with which it’s curated speaks of respect rather than commercialization. You don’t buy souvenirs here; you inherit echoes.

Upstairs, wide-plank floors creaked underfoot. The windows offered a modest view of the river and garden, just enough to remind those who worked here how far they were from London, or even from Auckland. It would have taken weeks to send a letter home. Those who stood in this room, handling shipments and calculating ledgers, did so in a world both vast and lonely.

5. Between Worlds: The Maori and the Mission

The missionaries who built these structures did not arrive in a vacuum. They entered a world already complex and ancient—populated by Maori iwi (tribes) with their own laws, customs, and spiritual beliefs. The land where the Mission House and Stone Store now stand was gifted by Hongi Hika, the powerful Ngāpuhi chief whose support allowed the mission to take root.

Hongi Hika was a man of both strategy and contradiction. He welcomed the missionaries, recognizing the potential of their tools and teachings. At the same time, he maintained traditional authority and led military campaigns that reshaped the tribal landscape. His dual approach to the missionaries—both patron and manipulator—underscores the delicate and often tense relationship between the mission and the Maori.

Artifacts on display in both buildings speak to this complex relationship. Taonga (treasured objects) like mere (short, flat clubs), carved wooden panels, and cloaks made of flax or kiwi feathers are displayed alongside bibles, ledgers, and British ceramics. These objects are not merely historical—they are conversational. Each one speaks to the crosscurrents of culture, power, and purpose that defined early colonial New Zealand.

6. The Garden and the Orchard: Cultivating More Than Crops

Behind the Mission House, a modest garden grows in tidy rows—beans, carrots, potatoes, and medicinal herbs. This is not a reconstruction; it is a continuation. The garden has been in continuous cultivation since the 1820s. The soil here is not metaphorical; it is literal history. Seeds planted by Charlotte Kemp and tended by her children still leave their memory in the scent of lavender and the texture of heirloom beans.

The missionaries introduced not only Christianity but also European methods of agriculture. Apple trees, in particular, flourished here, giving rise to Kerikeri’s later reputation as a fruit-growing region. A few of these early trees still survive, gnarled and bent but resolute. They are as much witnesses to history as any stone or timber.

The orchard, once a necessity, now feels almost like a chapel—rows of trees holding light in their leaves, bees moving from bloom to bloom, and the hum of something older than time. Walking among the apple trees, one senses the rhythm of a life that was at once disciplined and deeply intertwined with the land.

7. Stillness and Change: A Walk at Dusk

By evening, the grounds take on a different tone. The light bends longer across the river. Shadows stretch over the stone walls and the air grows cooler, tinged with the scent of damp earth and old wood. I wandered slowly between the buildings, the gravel crunching softly beneath my boots.

The stillness is not silence—it is the sound of preservation. Not everything here has been restored to its original form. Some things have been allowed to age naturally, to wear their time openly. Paint peels in corners. Floorboards bow. Iron catches rust. And yet, nothing feels forgotten. Every detail, every imperfection, feels like part of a long-held breath that will never be exhaled.

The river, always nearby, reflects the sky in changing colors. Ducks float without concern. A heron stands sentinel at the water’s edge. Everything here—human and natural—feels layered with purpose.

8. The Church on the Hill: Faith Etched in Timber

Up the hill from the Stone Store and Mission House stands St. James Church, a small wooden structure painted white and trimmed in forest green. Built in 1878, it continues the legacy of the Anglican mission but in a style that reflects the simplicity and strength of colonial religious architecture. The church is still active, its bell still calling out across the valley on Sunday mornings.

Inside, the pews are narrow and worn. The altar is modest, flanked by stained-glass windows that cast gentle patterns onto the wooden floor. I sat for a moment in the silence. The kind of silence that holds more than absence—it holds presence, a sense that countless prayers have soaked into the beams and floorboards.

The church overlooks the river and the buildings below like a watchful guardian. It connects the spiritual aspirations of the missionaries with the community that slowly grew around them. Standing here, looking down toward the Stone Store, I felt the full weight of continuity. Not just buildings preserved, but ideals carried forward—adapted, challenged, and still present in the weave of daily life.

9. Echoes Underfoot: Walking Home Through History

Night falls gently in Kerikeri. The stars arrive one by one, undimmed by city light. The last birds quiet down. The trees settle. The river flows, unhurried and unchanged. I walked back along the same path that had led me in, past the trees that had watched centuries unfold, past the river that had never stopped speaking.

Every step felt different. Not because the ground had changed, but because I had walked through stories not my own. Stories of faith and commerce, of land and water, of loss and renewal. The kind of stories that do not shout, but murmur. They do not demand to be known; they offer themselves only to those willing to walk slowly, to listen deeply.